Before the Broadsword: Recovering the True Identity of the English Backsword

Presented by Chris Connah, Independent Researcher

Identifying the Backsword

What is a Backsword? It is, of course a sword with a single edge. A sword with a ‘back’ if you will. Or, more specifically, an English sword with a single edge. Or an English sword with a single edge and a basket hilt. More commonly it is described as simply being analogous to a Scottish Highland Broadsword but with only one edge. George Silver uses the term interchangeably with the short sword and historic fencing masters in London seemed to use it exclusively to describe a single sword. The common belief does not coincide with the Earliest source that describes the sword and how to use it. For those who do not study the matter the answer seems reasonable enough. A sword with a back, a Backsword. Why would anyone need to believe anything other than this? Additionally, why would anyone need to make the distinction if the sword has the same overall form and function as the Broadsword? For those who do study the matter it should very quickly appear that the Highland Broadsword is too short, and the hilt design does not allow the sword to be used in the manner described in the source. This article aims to try and define the Backsword as it was according to the people who used it in history. It will investigate how the modern practitioner came to believe that the sword is synonymous with the Scottish Broadsword and will distinguish the one from the other.

The first written term of Backsword that is currently known, is Sloane MS.2530.[1]A manuscript that documents the history of a 16th century fencing school in London. The document begins recording in the time of Henry VIII. It is undated but appears to have been copied out in around 1570.[2] Without seeing the original document from which this one was copied we cannot be certain that the term was used earlier than that and so until further information arises, the term is from around 1570, possibly earlier. This document that provides a foundational reason for this discussion. The document reports a small history of fencing in London. It records the gradings of a number of students within its contemporary fencing community. These gradings are called ‘Prizes’ and record the progression of each student and the master under whom they had been trained. Within the document are detailed one hundred prizes of which eighty-eight are played by the recipient of the grade or rank. Not all the prizes were played for as some were awarded by agreement with the ancient masters or directly issued by the king. Of these 88 played prizes fifty are played with a Backsword.

The document shows that each prizor plays with various weapons. Popular weapons in the document are the quarter staff, the sword and buckler and the two-hand sword. Within Ms.2530 every prize that is played with only a single-handed sword is said to have been played with a Backsword.[3] No prize is noted as having been played with a Backsword and dagger or Backsword and buckler. Any prize that is played with a companion to the sword is noted as ‘sword and buckler’ or ‘sword and dagger’ only.

In the era of this record the Backsword is clearly an important weapon in the arsenal of the fencer. This continues to be the case as many British fencing treatises, continuing through the 17th and eighteenth century, still either mention or treat upon the use of the Backsword.[4]

The term also arises often in civilian life in plays, poems, histories and legal concerns though it seems it is never mentioned by soldiers. For all the treatises on war known to have been written in the 16th and 17th centuries in England only one uses the term Backsword (back-sword in the work). This book is called ‘The Art of War’ and is written by Edward Davies, Gentleman in 1619. This book is interesting in that it appears to be a reproduction of an earlier book called ‘The Art of War’ written by William Garrard, corrected and published by Captain Robert Hichcock in 1591. Whilst the two books are not identical to each other they seem to be the same work as many of the paragraphs are the same.

Both books describe how a pikeman should be armed with the earlier book describing that the pikeman should have a rapier and dagger, and the later book describing the pikeman having a Backsword. The soldier, unsurprisingly, most commonly uses the word sword. To the civilian the sword is an ornament, a display of status a cultural artefact even. To the soldier the sword is a tool. A functional part of the job.

Exploring definitions

In modern colloquial parlance the Backsword is defined as analogous to the Highland Broadsword though having a single cutting edge rather than the two of the Broadsword. Therefore, it would be prudent before offering a definition of the Backsword to offer a description of the Broadsword. This term is not to be confused with the earlier term broad sword in two separate words that describes the broadness of the sword, probably compared to its contemporaries. This term has been used for centuries to describe swords, and this use continues into the 16th century to describe something other than a Highland Broadsword.[5] Broad-sword as a hyphenated word or Broadsword as a single word is specifically a term to describe a type of sword whose use is attributed to Scottish warriors from the 17th century onwards. It is often termed a Highland Broadsword, Scottish Broadsword or Scottish Basket Hilt Broadsword for those who are looking to be very definitive.

It is relevant to note that the Scottish did not historically call it this. In Scottish it is called Claidheamh Mὀr which means Great Sword. This can often cause confusion as the Scottish also use a large two-handed sword that they gave the same name. The name is pronounced Claymore in English. This term is very rarely used in English to describe the Scottish Broadsword, and it is far more likely to be used to refer to the two-handed sword.

The Scottish Broadsword (Broadsword from here on will describe this weapon) is a basket hilted sword with a basket that is usually symmetrical in shape and has a blade that is between 33-35 inches in length. It is a sword designed primarily for cutting.

The earliest written mention of the Broadsword that is known to me is in the text that is also the earliest concise definition of the Backsword. It gives a definition of the Broadsword and within this text the two swords are in fact defined as distinctly different weapons.

There are several kinds of sword blades, some whereof are only for thrusting, such as the rapier, Koningsberg, and narrow three-cornered blade, which is the most proper walking-sword of the three, being by far the lightest; Others again are chiefly for the blow, or striking, such as the symiter, sabre, and double edged highland broad-sword; and there is a third sort, which is both for striking & thrusting, such as the broad three-cornered blade, the sheering-sword with two edges, but not quite so broad as the aforementioned highland broad-sword; and the English back-sword with a thick back, & only one good sharp edge, & which with a good point, & closs hilt, is in my opinion the most proper sword of them all for the wars, either a foot or on horse-back. That therefore a man may the more easily know, what are the best qualifications belonging to a good and useful sword, he needs only consider a little the following principles, which relate to it.[6]

If William Hope defines the Backsword and the Broadsword as two distinct weapons, then how has the conclusion been reached that they are synonymous with each other aside from the number of cutting edges?

This question could possibly be answered by the work of respected historian and once curator of the Royal Armouries, Claude Blair. In his book European & American Arms c. 1100-1850 Blair states, whilst talking of the Broadsword

‘The Backsword is indistinguishable from the Broadsword, except that it has a single blade (i.e. a blade with a back), and will not therefore need to be discussed separately’.[7]

Blair gives no citation for where his definition of ‘blade with a back’ comes from. It is possibly this phrase from this book that has cemented the belief that the Broadsword and Backsword are synonymous, although no other author since has cited this as their source and so it is equally plausible that people have formed this conclusion for themselves.

Blair was studying weapons as objects of archaeological and cultural significance just before the rise of the study of European Martial Arts led to a new type of study for historical weapons. The study of their use. In the early 1990’s historical treatises describing the martial arts of European nations of the 14th-18th century were re-discovered and various groups began trying to decipher them and bring these lost arts back to life.[8] The first book of this renaissance of traditional martial arts published on the English martial system was ‘English Martial Arts’ by Terry Brown, published in 1997. In this work Brown describes his interpretation of the English fencing system as described by 16th century author and swordsman George Silver. In this work Brown also casually states that a Backsword is ‘A Broadsword with only one cutting edge’.[9] Brown also does not give a citation for why he believes that the Broadsword and the Backsword are synonymous except only for the number of cutting edges.

Paul Wagner suggests the two weapons are the same based off the works of George Silver and apparent conjecture from there

‘Silver describes the single-handed sword as a “shortsword”, a term that contrasted it to the hand-and-a-half “longsword”. Such weapons could be either a “broad sword” with two edges, typically associated with the Scots, or a “back sword” with a single edge and thick back, more typically English in style. In Brief Instructions Silver seems to use the terms “short sword” and “back sword” interchangeably, but elsewhere he talks of “short swords and Bucklers & back Swords” suggesting that his favoured “shortsword” was a “Broadsword”.[10]

Stephen Hand suggests

‘Swords of this period had blades of two distinct forms. The Backsword (literally a sword with a back) had a wedge shaped blade with a single edge and a wide blunt back. The blade normally became double-edged between half and two thirds of the way down the blade. Double-edged swords, soon to become known as Broadswords had two cutting edges for their full length. The two types of weapon handle almost identically.’[11]

Identifying the weapons as handling in an identical manner and form, one of two distinct blade forms in the time of George Silver. Hand sees only the form of single and double edged rather than Hope’s three distinct forms based on use.

Searching the definitions and etymology of the word show no archaic sources for the definition, not even William Hope from the early 18th century. According to Dictionary.com the term Backsword means ‘a sword with only one sharp edge; Broadsword’. The earliest written reference to a Backsword that I am aware of is from 1582 in a publication titled ‘A remembraunce of the pretious vertues of the right Honorable and reuerend Iudge, Sir Iames Dier, Knight, Lorde cheefe Iustice of the Common Pleas.’ By George Whetstone.

‘The Lawyer lewde (as many naughty are,)

And yet the law, to cloke their wrongs do straine:

He thus would check, this string my frend doth iar

You of the Lawe would make a Backsword faine,

For others eg’de, for your offences plaine.

You can by lawe, vnpunisht steale a Farme,

But mend, or hell will sure your catcas warme.’

This passage describes the way a lawyer might strain the extremes of the law to cover their wrongdoings. The Backsword reference uses the Backsword as an analogy, quoting the imitation of the Backsword to describe the lawful but unjust theft of property on the blunt side, being punished on the sharp side in death by a trip to Hell. A similar analogy is used again in another book by Whetstone called ‘The English Mirror’ published in 1586.

‘and Iustice would chasten the concealed fault, if she could commaund the Law, and such is the cunning,of pollitike Lawe breakers, that where the ignorant are hanged for stealing of a sheete, they will haue the Lawe to strengthen them, in the robbing of a mans inhearitance, and therefore is Lawe likened to a backe sworde, eadged and sharpe, to chasten the simple offender, and blunt when the subtill shoulde bee corrected’

In this passage the Backsword clearly only has one edge. So much so that it is being used as analogy for the imbalance inherent in the justice system, sharp for the ignorant but blunt for the politician. This analogy is probably the most common usage of describing the Backsword as being single edged. It appears repeatedly in 16th and 17th century references. These passages do not equate the Backsword to the Broadsword, nor do they give any other description. The intended reader must presumably be familiar with the weapon.

In 1609 in a sermon read for King James VI/I by one Thomas Playfare, the same analogy of the Backsword as Whetstone is used, though in this case not for law but for the humility demonstrated by Jesus but missed by many since. The analogy being that those who practice what they preach demonstrate like a two-edged sword, taking the hardships offered by their integrity whereas many would rather behave as a Backsword, teaching humility (the sharp) but showing none (the blunt).

‘Therefore there is no teacher to me, there is no master to me: Learne of me, because I am meeke and humble in heart. This kind of instruction both by teaching and by doing, is that two-edged sword, which proceedeth out of the mouth of the Lambe. For tell me I pray you (if it be no trouble to you) tell me, what is the reason think you, why so many Preachers in their Churches, so many masters in their families, seeke to redresse abuses, striue against sinnes, and yet preuaile so little, but onely because they fight not with this two-edged sword, but with a Backsword. The sword which they fight withall is very sharpe, and cuts deepe on the teaching-side, but it is blunt and hath no edge at all on the doing-side.’[12]

Once again, the analogy does show that the Backsword has only one edge. This one has the added addition of the mention of a two-edged sword alongside the single. Whilst these examples show the common understanding of the Backsword to be a single edged weapon, that is the extent of any definition they offer. None of these historical references describe the sword beyond the cutting edges of the blade. At this point it could simply be any sword with only a single edge.

In 1649 an English-Latin dictionary translates Backsword as ‘Machaera‘. This word is from the greek word ‘Μαχαίρι‘ (Machaíri) which means ‘knife’ and in Latin means the same. In this book is the author continues to translate for Scimitar, Falchion and Hangar, all single edged swords. This Latin dictionary demonstrates that the Backsword is a recognisable weapon, distinct not only from various types of other single edged swords but also from double edged swords which seem to all fall under the category of ‘sword’. Preferring in fact to refer to the Backsword as a ‘knife’.[13]

The next definition comes from a book called ‘The second part of the new survey of the Turkish empire’ by Henry Marsh (1664).

‘As for their armes which hath been touched before something more particularly is to be said of them. They differ from those of the Europeans very much, yet their Harquebuze is something like our Caliver, their Scymetar a crooked flat Backsword, good at Sea upon Boording, or among Ropes, but in field fight is much inferiour to the Rapier’[14]

This passage describes the Backsword as having a straight blade rather than the ‘crooked’ blade of the Turkish scimitar but likely still single edged. An interesting note is that the scimitar is also ‘flat’. This may refer to the thinness of the blade or broadness of the blade compared to a Backsword. It is unfortunately not clear enough to be certain and does not appear to be relevant to the scope of this article.

There is a common theme of colloquial reference to the Backsword being a single edged sword, distinct from falchions, scimitars and hangers. The next source throws a spanner into the works though. In 1677 there was published a French-English, English-French dictionary, in which the following terms are defined;

- ‘BADELAIRE (en terme de blazon) coutelas, cimeterre, a short and broad back-sword, being towards the point like a Turkish Simetar.’

- ‘A back-sword, epée qui n’a qu’un trenchant, un coutelas.’

- ‘A two-edged Sword, une epée à deux trenchans.’

- ‘CIMETERRE (m.) sabre, a Simitar, a kind of short and crooked Sword much in use among the Turks.’

- ‘Coûtelas (m.) a Cuttelas, or Courtelas, a short sword for a man at arms.’

- ‘A Hanger, or short crooked sword, un coutelas.’

- ‘SABLE, a kind of short and crooked sword, un sabre.’

A badelaire, which is a cutlass, also a Backsword. A Backsword, which is a cutlass. A hanger, which is also a cutlass. These definitions all seem to suggest that the Backsword is synonymous with the cutlass and hanger, contrary to the earlier description. A cutlass does not have to be curved but in this definition appears to be due to the fact the hanger is noted as being crooked and then called a cutlass. The sabre, hanger and scimitar are definitively curved blades. This could mean a few things. First is that the Backsword is indeed both single edged and curved. The second is that the cutlass is not curved, except when it is. Or the best way to describe a Backsword to a Frenchman is to relate it to the cutlass or sabre regardless of the shape of the blade.

This complicates things as a Backsword can be anything that has one edge and is straight or curved but it is not flat. It is distinct from the falchion, scimitar or hangar whilst simultaneously being similar to these weapons. This is the unfortunate result of trying to define something historical that did not require defining in its own time.

The above definition and the Latin translation are trying to communicate into a foreign language what a Backsword is and so they are not necessarily giving a true definition, rather they are just trying to make the reader understand. Neither French nor Latin have a term for Backsword and so the definition must, necessarily use something that would be familiar to speakers of those languages. To this end the Backsword is a commonly known word and item to the English culture that any foreign person might need to have translated but it seems also to cover a wide variety of items. The other sources I have cited show a colloquial use of the term to mean a sword with one edge with no further definition.

William Hope, in his work ‘A New, Short, Easy Method of Fencing’ gives a true definition and defines the sword according to its use as well as separating it from other contemporary sword types. It is very late in the story of the Backsword, being from 1707, some 200 years after the word is first written down but Hope’s definition is very clear. A single edge sword, with a closed hilt and better for war than any other sword. Interesting then, that Soldiers don’t tend to use the word. The soldiers who are treating on war in the 16th and 17th centuries tend to either recount famous battles or describe how the modern army ought to conduct itself. In the latter case the only thing relevant to the author is that the soldier carries a sword. The sword is important to the soldier as it is the last port of call when all else has gone awry. They often note the length required as that is important to a soldier, especially when people are bringing swords that are too long, but the form of the sword outside of that is not a major concern for a soldier.[15]

Historians say that a thing is not defined until it is dead. That is to say that before Hope, no-one needed a definition of the Backsword to be written down as it was well enough known by people. An author could write ‘Backsword’ and know their audience would understand.

Morphology of the Backsword

As Hope defines three different types of swords it is time to investigate the mechanical function of the sword to understand the typology he is using. Swords are more usually named according to their form rather than their function and naming conventions are usually simple, the smallsword is a small sword. It is typically smaller than swords that are contemporary to it. A Longsword is harder to define, there is the medieval longsword that is named for the length of its handle rather than the length of its blade but in George Silver’s work he notes a long sword with no description but likely refers to a single handed sword with a long blade as he usually groups it with the long rapier. Broadsword is specifically for a typical Scottish weapon that has a blade that is broader than many of its contemporaries. The rapier is a long and drawn-out discussion as to what constitutes a rapier, where the word comes from and what the weapon is used for. Italian warriors begin to realise that thrusting is very efficient and so they begin to develop their systems of fighting around it. As the fighting systems develop the swords begin to develop to accommodate the system. Italian society begins to move away from warrior culture to mercantile culture. The sword moves more to a use of personal self-defence rather than military requirements. Range becomes more appropriate and so the swords get longer. Concurrently swords get obnoxiously long and fighting systems develop further requiring lighter swords. By this time other nations have picked up the idea and developed their own versions of both system and weapon. From this point the influence travels back and forth.

During this history, spanning at least 100 years, the rapier changes repeatedly to accommodate variations of style and fashion. The word, however, is still steeped in mystery.

The naming convention attached to the Backsword is also a mystery. Of course, Blair suggests that the sword ‘has a back’ but Blair is not a contemporary user of the sword. It could be that there are techniques that specifically use the back of the blade. To properly define the Backsword, it would be prudent to look at the way it is used by the fencers who use it in its own time. There are many treatises on fencing from Great Britain which are the best place to try and find out how the weapon is used. These fencing treatises range from the 16th century to the 18th. The term is common but appears in less than half of them. It is never defined by anyone other than Hope. It is arguable that Silver defines it to a point but only states the length of the blade and strength of the hilt and agrees to the cut and thrust nature of the weapon. In this, he gives little in addition to Hope. It is useful that he gives us a similar definition showing that the sword and the terminology appear consistent throughout history. There is more to consider with regards to the thought that the Backsword and Broadsword are the same weapon and that is that two later fencing masters call them the same thing in their treatises. Although both presume the weapon to be English, meaning the term ‘broadsword’ may have been used to describe an English weapon as well as a Scottish one by the 18th century.

In 1711 a gentleman by the name of Zachary Wylde wrote his treatise ‘English Master of Defence’. In this work Wylde equates the Backsword to be synonymous with the Broadsword as he states, ‘Back or Broad-Sword is a true English weapon and first made use of in this nation’. Wylde discusses the use of the Backsword in both cutting and thrusting within his treatise.[16]

Andrew Lonnergan does the same in 1771 in his ‘The Fencer’s Guide’ stating ‘if your desire still leads you after a knowledge of the use of any other weapon, I would prefer that of our English broad, or back-sword…’. In Lonnergan’s work he describes the use of the basket of the weapon. It is difficult to understand if he uses thrust, but he speaks of ‘Throwing’ guards at the opponent which I believe could be using the guards as a thrust. This is the only reference to the two weapons being the same. Further fencing masters continue to mention the weapon.

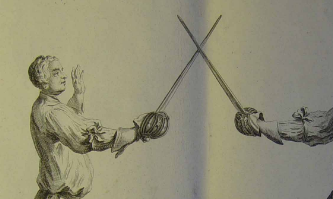

Donald McBane wites his treatise in 1778 called ‘The Expert Swordsman’s Companion’ in which he treats on the Backsword nestled very clearly inside the chapter on the spadroon or shearing sword. McBane does speak of both cuts and thrusts in his treatise on Backsword but no other description. His work does have an image at this point of the book where both fencers are holding what would be described as Broadsword of the Scottish design.

Captain James Miller has a short work on the science of defence in which he uses the word backsword similarly to the ancient masters of defence. With a companion weapon, the sword is known as a sword, alone it is a backsword. This treatise is made up primarily of pictorial ‘plates’ which show in detail the sword being used. The sword is of the symmetrical basket and short bladed style usually attributed to the Scottish.

At this point the Backsword can either be synonymous with the Broadsword or a separate type of weapon. The 18th century is late in the development of the weapon, and it is plausible that the term has changed over time. Which is about as helpful as the dictionary definitions mentioned earlier. Aside from Hope no others describe the Backsword as having a single cutting edge though they do describe it as a cut and thrust sword.

The 17th century gives us only two treatises that mention the Backsword. That is ‘The Noble and Worthy Science of Defence’ by Joseph Swetnam in 1617 and ‘The Private Schoole of Defence’ by George Hale in 1614. The former is a treatise on the whole science of defence and the latter a criticism of fencing schools for their methods of teaching. Neither of these treatises mentions the Broadsword.

Hale does not describe the number of cutting edges of the Backsword should have but does clearly expect it to be a cut and thrust sword as one of his criticisms is the same as those of George Silver in that the fencing masters are teaching only the cut with the Backsword and only the thrust with the rapier. Hale also only mentions the Backsword as a single weapon and shortens to just sword when speaking of a sword with a companion. He only mentions Backsword once and uses the term Short Sword throughout the rest of his work. Swetnam on the other hand does give us a view of the number of cutting edges the sword should have.

‘Now although I heere speake altogether of a Backe-Sword, it is not so meant, but the guard is so called: and therefore, whether you are weaponed with a two-edged Sword, or with a Rapier, yet frame your guarde in this manner and forme, as before said’[17]

As he sees the need to clarify that you may have a two-edged sword, we can infer that he presumes that a Backsword has only one edge. Swetnam also describes the use of both cut and thrust with the Backsword.

The Prime suspect of the 16th century for the use of the Backsword is George Silver. A gentleman who entreated on the use of the short sword and compared it to Italian rapier fencing that existed at his time in England. It is from the interpretations of George Silver’s work that we most commonly see the use of the term Backsword in our own time. The term Backsword is sparse in the works of George Silver, so it is unclear how his work managed to become the epitome of Backsword fencing. The term is only mentioned once in Silver’s first book, Paradoxes of Defence, in a passage where a hypothetical Italian is setting forth their reason for the superiority of the long rapier.

‘Strong blows are naught, especially being set above the head, because therein all the face and body are discovered. Yet I confess, in old times, when blows were only used with short Swords & Bucklers, & Back Swords, these kinds of fights were good & most manly, now a days fight is altered. Rapiers are longer for advantage than swords were wont to be. When blows were used, men were so simple in their fight, that they thought him a coward, that would make a thrust or a blow beneath the girdle. Again if their weapons were short, as in times past they were, yet fight is better looked into these days, than then it was.’[18]

This passage says nothing for the form of the back sword only that it was used concurrently with sword and bucklers. It suggests a time when warriors in battle used only cuts and not thrusts in stark contrast to the criticisms of both Silver and Hale in relation to the use of the weapon.

The next mention of the Backsword from Silver appears in Brief Instructions. There are two mentions, but both sit in the same context, which is simply referencing a technique back to a different portion of the book.

‘You must neither close nor come to the grip at these weapons, unless it is by the slow motion or disorder of your adversary, yet if he attempts to close, or to come to the grip with you, then you may safely close & hurt him with your dagger or buckler & go free yourself, but fly out according to your governors & thereby you shall put him from his attempted close, but see you stay not at any time within distance, but in due time fly back or hazard to be hurt, because the swift motion of the hand being within distance will deceive the eye, whereby you shall not be able to judge in due time to make a true ward, of this you may see more in the chapter of the back sword fight in the 12th ground of the same.’[19]

‘Every fight & ward with these weapons, made out of any kind of fight, must be made & done according as is taught in the back sword fight, but only that the dagger must be used as is above said, instead of the grip.’[20]

There are only three chapters in Brief Instructions that have 12 or more grounds,

Chapter 4, Of the Short Single Sword Fight Against the Like Weapon

Chapter 8, Of the Short Sword and Dagger Fight Against the Long Sword and Dagger or Long Rapier and Poiniard

Chapter 11, Of the Short Staff Fight, Being of Convenient Length, Against the Like Weapon

The last one can be easily eliminated as being the chapter to which Silver is referring when he refers us to the chapter on the Backsword fight as it relates to the staff and not to the sword. The other two do relate to swords so can the 12th ground of either be related to the above quote?

Ground 11 of Chapter 8 speaks on how you should behave against an opponent who is in the ‘Stocatta’ ward. It warns to be wary the opponent does not take control of your weapon with their dagger as this would leave you reliant on the protection of only your dagger. It does not in any way discuss closing or gripping nor does it discuss how to make a true ward.

Ground 12 of Chapter 4 describes that if a person who has fought upon only one fight insists on continuing to press in upon you then you may safely grip them. It continues onto a second paragraph that describes that if you have a dagger or a buckler then you can, instead of gripping, hurt your opponent with your offhand weapon.

From this we can deduce that the chapter ‘on the Backsword’ to which Silver is referring is the chapter on the short sword against the like weapon. Although Silver does not give us a description of the Backsword, we can see that he equates its use at the very least, to be identical to the use of the short sword. It would not be unreasonable speculation to posit that he equates the form of the two weapons to be the same as he calls chapter 4 ‘the chapter on the Backsword’. We can note a few things that differ in Silver’s account to those we have seen in this article.

The first is that the use of the weapon is identical to the short sword and so the Backsword is indeed a cut and thrust weapon which seems to match that which was described by Hope and Swetnam. Silver’s system of fighting is definitively cut and thrust as he when he is asked which is better, a cut or a thrust, he responds that the ‘question is not propounded according to art as no fight is perfect without both’.[21] This follows from Paradox 12 which is titled ‘Perfect Fight Stands Upon Both Blow and Thrust, Therefore the Thrust is not Only to be Used’. Both these paradoxes clearly define the use of both cut and thrust.

The most compelling source, that has the most unsettling use of terminology, that really questions the way the term Backsword was used in its earliest days is the Sloane manuscript Ms.2530, mentioned previously. Of the 88 prizes that are noted in this record 50 of them are played with the Backsword, 43 are played with sword and buckler and 10 are played with sword and dagger. 16 prizes are played with both Backsword and sword and buckler, 4 are played with both Backsword and sword and dagger. A further prize is played with both Backsword and rapier and dagger.

The significance of the prizes played with both arises when it is noted that at no point is the Backsword ever described as having a companion weapon and at no point is a sword with a companion weapon called a Backsword. The document records the Backsword as a single sword never used with a companion. If the suggestion that the Backsword must be single edged is true then no less than 17 prizors within this document have brought two swords with them to their prize, one single edged sword for using alone and a double-edged sword for using with their buckler or with their dagger.

It is plausible that everyone in this document has more than one sword as those that are playing their prizes with the Backsword will also be playing at the long sword or bastard sword. Potentially they are borrowing swords form their master as this is something that is noted in Ms. 2530.[22] Seven prizes are played with rapier and dagger and sword and dagger or sword and buckler with one of these being played with rapier and dagger, sword and dagger and Backsword. In these instances, we can see that the prizor brings at least two swords, the rapier and the sword but one of these must then also have brought a third sword, a Backsword. This prizor also played at the longsword so would have brought four swords in total. However, as Silver equates the Backsword to being identical in use to the short sword it seems superfluous to bring a short sword and a Backsword as well as your rapier and your two-hand sword.

The number of swords that each person brings to their prize is not exactly the concern here for the most part as it is possible that the prizors could have owned more than one sword. Many people did and this was their hobby after all. The question is whether there are any techniques with the single sword that utilise the single edge of the Backsword that are then not used with the companion weapon that would give an explanation for the terminology in Ms.2530.

Within Silvers work there is only one technique described that specifically uses the back edge of the sword and that is in Paradoxes of Defence;

‘The sword and buckler, and the sword and dagger are double weapons, and have eight wards, two with the point up, and two with the point down, and two for the legs with the point down, the point to be carried for both sides of the legs, with the knuckles downward, and two wards with the dagger or buckler for the head.’[23]

The two wards for the legs have the point of the sword down and the knuckles also downwards. Describing the position of the knuckles is a common parlance in old fencing treatises to describe the position of the hand. In this description the ward appears to be a movement of the sword to defend the legs from an attack. The ward is the same on both sides, and the position of the hand remains the same. Thus, if I have my knuckles down, with my sword in my right hand the front edge of my sword blade will be facing towards my left. As such if I keep my knuckles down and move my hand to the right to defend my right leg, I will be using the back edge of the blade to make the defence. Usually, a fencer wants the front edge of their sword facing their outside so a technique on the left will have knuckles down and, on the right, knuckles up.

This technique is noted by Silver as an additional ward for use with the sword and dagger. It does not demonstrate a use of the back edge of the sword when used alone, rather that it uses the back edge of the sword specifically with the dagger or buckler. This brings into question the possibility that the masters of defence are using the term Backsword for a single edged sword because it would be used differently to a sword with a companion weapon. Both George Silver and the Masters of Defence of London see the Backsword and the two-edged sword as the same thing.

The masters of defence do not describe if they are using the Backsword as a cut and thrust. According to the criticisms of Silver and Hale, perhaps not. This does not mean, however that the sword is not designed for both. To everyone else, the Backsword is, as Hope described it, for use as a cut and thrust sword. This means not just that it is used for cutting and thrusting but rather it is mechanically different to swords for cutting and swords for thrusting.

The Mechanics of the Cut and Thrust Sword

The mechanics of the cut and thrust sword is a topic that requires a lengthy discussion too great for this article. None the less a brief description is required as it is foundational to the theories in this article. As Hope has described three different types of swords that separate the cut from the cut and thrust and separates the Backsword from the Broadsword, there must be a reason. A physical, mechanical difference between the three types of blades. The difference is the way mass is distributed throughout the sword. The laws of physics affect the sword in the same way they affect any object. The mass distribution will change the natural axis of rotation of the blade when it is moved by the introduction of energy, or a point load.[24]

The closer to the tip of the blade the mass is, the more torque is needed to begin the sword moving in angular rotation. The moment of inertia of the blade will be high. If the mass is concentrated near to the hilt, then the rotational inertia will be less, and less torque will be required to get the sword moving. Equally a sword with a high moment of inertia will be difficult to stop moving once it begins rotating. A pure, perfect cut and thrust sword will have its axis of rotation exactly on the centre of the blade.

A blade that has its mass concentrated towards the tip will be better for thrusting for two reasons. The first is that it will take too long and too much energy to begin a rotation of the blade for a cut so it will be more efficient to use in thrusting motions. The second reason is the same as the first but from the point of view of the defender. It will take a larger amount of energy to impart a rotational movement of the blade and change its course to defeat the thrust. This may be why both Silver and Hale speak of short rapiers. Even a blade of convenient length can have the mass concentrated nearer to the tip and thus will behave as a thrusting weapon.

The opposite would be the case for a cutting sword. Defeating a thrust will be effortless for the defender but the speed of rotation will make the cut difficult to keep up with to parry. Such a sword can swiftly change direction and adjust to defeated attacks. Whilst it is easy to stall the rotation of such a sword, so is it easy for the user to begin a new rotational motion, a new cut.

When moving just the hilt on these swords you also get a different response. Moving the hilt of a tip heavy sword will likely leave the axis of rotation in place. The hilt and the strong of the blade will move offline but the tip will stay close to where it began. You can see this utilised in historical rapier fencing treatises when the hilt is used to move the opponent’s blade offline before thrusting. Moving the hilt of a sword with its axis of rotation closer to the hilt will do the same but for the opposite result. The hilt will move, the blade will rotate around the axis of rotation and impart a great speed and large circle on the tip of the blade. This can be seen with cutting style fencing such as Broadsword and sabre. It is also much easier on swords of this style to simply impart the rotation around the wrist of the user as the counter torque from the axis of rotation will be minimal. The strong part of these swords is much smaller than those of the thrusting or cut and thrust swords and so to parry a cut from another sword the parry needs to be made near to the hand. This is why cutting swords tend to have high levels of protection over the hand in their hilt designs.

The cut and thrust sword rotates around the centre and so is a balance between these two sword types. The thrust is less strong than the thrusting sword and the cut is much slower than the cutting sword. The length of the strong part of the blade allows the parrying of cuts further from the hand as well as strength to push an incoming thrust offline so the cut and thrust sword defends well against both, if used according to its strengths.

All swords exist on a scale between cut and thrust which means that there is no clear line between one and the other and distinguishing one from another is somewhat subjective. The cut and thrust sword is more adaptable than swords at either of the two extremes. The cutting sword and the thrusting sword are specialised for their given tasks. The cut and thrust can more easily utilise a thrust against a cutting sword or cuts against thrusting swords. It is able to do whatever it needs to achieve its goal where the swords of the extremes are limited in their actions.

The Closed Hilt

The term ‘basket’ hilt refers to many different designs across a large portion of history but can best be explained as a hilt that has up to four panels covering the hand. English basket hilts tend towards having between one and four and Scottish hilts almost exclusively utilise four. As a cut and thrust sword, a Backsword does not technically require a basket hilt but there does seem to be a preference in England from the 16th century to have a basket hilt on swords. This appears to be a fashion from Northern Europe, and it is likely that the English fencing system is influenced by the Northern Europeans more so than Central European. In Central Europe hilts tend to be in front of the quillon and George Silver sees the Italian fencing that has come into England as contrary to his native system of fencing. Silver’s concern is mainly for the length of the Italian weapons and the civilian nature of their fencing but he does note that even the ‘rapier of convenient length’ is inadequate due to a ‘lack of hilt to defend the hand and head from the blow’.[25] The hilt being in front of the quillons is advantageous to fencing that prefers thrusting by creating a larger angle between the opponent’s blade and the user when opposing a thrust with blade engagement. These hilts are designed to be advantageous to thrust oriented fencing, working in the opposite manner to the closed hilts of cutting swords.

From the 16th and 17th centuries only one discourse on war mentions the Backsword hilt and that is the aforementioned ‘The Art of War’ by Edward Davis. In which Davis only offers a Backsword with an ‘Irish Hilt’.[26] In Francis Markham’s ‘Five Decades of Epistles of War’ from 1622, Markham confirms for us that the Irish hilt is indeed of a basket form.

‘He shall have by his left side a good and sufficient sword with a basket hilt of a nimble and round proportion after the manner of the Irish’

The term Irish hilt is almost as common in the 17th century as the term ‘Backsword’. This is likely attached to a change in the monarchy in 1603. When a new monarch takes a throne, they tend to bring their own courtiers with them. The friends and family who will become their own privy council. In the case of James Stewart taking the throne of England, this is indeed the case. It is at this point that the English begin to refer to the Scottish as ‘Irish’, particularly the Highland Scots who speak the ‘Irish’ language. Lowland Scots referred to themselves as English at this time. It is likely that it is around this same time that the Scottish take a fancy to the basket style hilt and take it for themselves.

Whilst there is no mention by 16th century soldiers of the Backsword, there are two who describe the hilts of the swords that they recommend that soldiers should carry. All soldiers seem to agree that the sword’s blade should be a yard in length, the same a Silver suggests, but they do not all agree on the hilt style. In 1592 Humphrey Barwick writes that the type of sword a footman should use is ‘a good strong sword of a yarde in blade, and no hilts but crosse onely, a dagger of ten or twelue inches in blade and the like crosse hilt’.[27] Whilst in 1594 Sir John Smythe suggeststhat the hilt of the sword should be ‘only made with. 2. ports, a greater and a smaller on the out side of the hilts, after the fashion of the Italian and Spanish arming swords’.[28] Whether or not any soldiers took heed of the advice or whether they called them Backswords is not known but not only basket hilted swords are being used by the English at this time.

William Hope comes to our aid once again from the 18th century to describe the basket hilt in his New Method of Fencing he perfectly describes the hilt of the Backsword.

‘I advise all master, who shall undertake the teaching of this new method, with success, that they order their scholars, to provide themselves with fleurets having hilts, with several neat bars, both lengthways and a cross upon them, resembling somewhat the closs-hilts of back-swords, for the better preservation and defence of their sword hand and fingers.’[29]

English soldiers in the 17th century use what is now referred to as the ‘mortuary’ hilt which is a basket style hilt and exists in popularity alongside the increase in the use of the term Backsword. It is not certain when the Mortuary hilt came into use, but it was likely influenced by the trends in the Low Countries brought back from the eighty years war where many English soldiers fought in the Elizabethan era. It is also in the 17th century with the that hilt designs begin to lose their quillons.

Rapiers often lose their front quillons and the English mortuary hilt and Scottish basket hilt lose both, sometimes keeping a vestigial rear quillon. This is likely due to changes in the fencing methods being used with the swords and is a subject for its own research. The increase in thrusting fencing could be a part of this as many hilts in this era begin to add solid plates between the hilt and the blade.

At this point there has been a surprisingly small use of the term ‘basket’ in relation to hilts and both Silver and Hope use the term ‘closed’. Of course, baskets are not the only type of closed hilt. At this point there is also no source that specifically uses the term basket hilt in relation to a Backsword. Irish and closed but not specifically basket. What then, is a closed hilt?

There is an argument to be made that Spanish cup hilts entirely close in the hand and fingers from attack. Swept hilt rapiers could be considered a design that is closed. The bars of the hilt cover the hand at least as much as some of the basket hilt swords of English heritage, sometimes more so. They do allow for the forefinger to be placed over the quillons and in Silver’s work he offers the opinion of an imagined Italian who decries the English hilts for not allowing the finger over the cross so that seems like any other reasonable criteria for a closed hilt.[30] As discussed earlier, Germanic style swords and swords that have a greater preference to cutting have their hilt protection placed behind the quillons rather than in front. Let that be a second criteria. A hilt design with the protection behind the quillons that does not allow the finger to be safely put over the crossguard of the sword

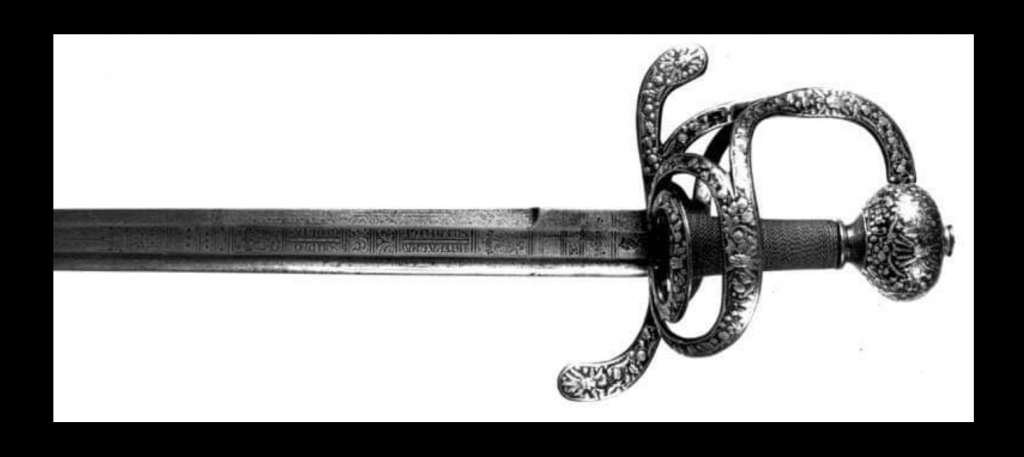

There is a hilt style from England that is little known. It is of flat bar construction with the bars closing over the top of the hand in a similar manner to the cup hilt of Spanish swords although it does not close around the hand (figure 4).[31] The hilt design is usually described as ‘Early 17c’. Other styles of hilt can be seen to be used in the time of Elizabeth I. In the painting ‘Procession Portrait of Elizabeth I’ six out of the seven gentlemen have swords that do not appear to be designed to have the finger over the crossguard. Three of them seem to be very similar in design to those seen in Joachim Meyer’s 1561 manuscript on the use of the ‘Rapier’ and one is very similar to the design of hilt seen in Meyer’s 1563 work on the same. Aside from the Meyer type, these hilts may be considered closed by the definition used here though not baskets. The painting of these hilts is a little obscure in their detail and perspective, but I believe this is the style of hilts they are depicting. The existence of these swords confirms not only the Germanic influence on English fencing but that also English Gentlemen of Elizabeth’s court were still wearing swords designed for traditionally English fighting as well as those who were choosing to wear Rapiers. Rapiers are common in portraits of 16th century gentry but that could well be simply because they are fashionable. Portraits are designed to show off the subject and fashion was very important to the gentlemen of the Elizabethan court. The hilts of the swords in the procession painting are as ostentatious as many rapier designs.

The design in Meyer’s 1563 work is actually a very simple hilt design. A crossguard with a knuckle bow and a single side ring on the outside of the sword. There is a variation on that hilt design that does seem distinctly English. On the sword that was gifted to Sir Francis Drake by Queen Elizabeth I the hilt is very similar to the Meyer design aside from one small detail. On this hilt the bar that forms the side ring curves down to the middle of the knuckle bow rather than meeting with the quillon. Another example of this sword can be seen in Claude Blair’s ‘European and American arms c1100-1850’.[32] This hilt design is one I have used myself and I find that in single combat the hilt offers the exact same protection as a full basket hilt. This hilt seems to be an English addition to the Germanic design in Meyer and as such is added here.

George Silver is often credited with advocating for the use of a basket hilted sword he does not ever actually describe the hilt as a basket nor as being closed. At least not in relation to the sword. He does say ‘if you have a gauntlet or closed hilt upon your dagger hand’. Of the sword he states in Paradox 23 on the advantage of the short sword

‘And what a good defence is a strong single hilt, when men are clustering and hurling together, especially where variety of weapons are, in their motions to defend the hand, head, face, and bodies, from blows, that shall be given sometimes with swords, sometimes with two handed swords, battle axes, halberds, or black bills, and sometimes men shall be so near together, they shall have no space, scarce to use the blades of their swords below their waist, then their hilts (their hands being aloft) defend from the blows their hands, arms, heads, faces and bodies. Then they lay on, having the use of blows and grips, by force of their arms with their hilts, strong blows, at the head, face, arms, bodies, and shoulders’[33]

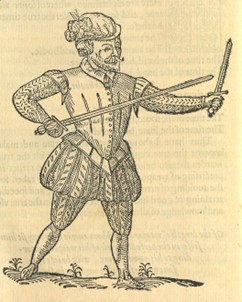

In which Silver describes the hilt being strong and protecting the head and hand from attacks with the hand held high and even using the hilt to attack the enemy when there is no room to use the blade of the sword. Whilst this does not definitively describe a basket hilt, such things would be better achieved with one, and whilst Silver does not actually describe the basket hilt, it is not possible to argue that he did not draw one!

Okay, he probably didn’t draw it himself, but Silver’s work has one single image. This image is used to assist the reader in knowing how to correctly measure the length of their sword according to Silver’s description. It is unquestionable that in this image the hilt of the sword being held has no less than three vertical bars covering the hand and appears to be a depiction of a basket hilt.

The basket hilt is a very common and fashionable design of hilt in England but so too are other hilt designs that are closed as well are others still that are not closed. It is impossible to say if the English of the 16th or 17th century would have called them all Backswords, but I feel like they fit the bill.[34] Putting the finger over the cross is very much a central European trait and there is no reason the English would use a hilt that allows such a thing when they can have protection instead. At least not outside the bounds of fashionable rapier fencing.

Let’s now address the elephant in the room. The blade of the Backsword. It is a sword with a back. A single edged sword. There is no other way, all the evidence points to this, right?

Well…. Unfortunately (because I obviously wrote this whole article with no biases whatsoever) yes. The most common reference to the Backsword having a single edge is as the analogy for the legal system. That it is sharp for the poor man and blunt for the rich. This analogy appears over and again throughout the 17th century. There is one single source though that may throw a spanner in the works;

‘And he followed this blow with all the might he had, by endeavoring to put it in practice on John King of England, and Philip Augustus King of France. But the truth is, he wanted the Welch-mans Back-sword with two Edges, for he neither had the true Bilbo-blade, Temporal Power, sufficient to force obedience: nor yet the Sword of the Spirit, Rightful Authority, to do what he did. He only sent out his Voice, yea and that a mighty voice, by thundring out his abominable Excommunications, which only proved to be vox & praeterea nihil.’[35]

This on its own is not enough to deny that the Backsword has one edge as it could be read as though he wanted the Welshman’s Backsword, but with two edges instead of the one it currently has rather than the Welshman’s Backsword already having two edges. Sources from the 16th century are scant, and repetitive or vague in the 17th. The 18th century gives us William Hope’s definition and two other masters making it both synonymous with the Broadsword and English. The latter two centuries conclude the single edged nature of the weapon and so at least we might conclude that during this time, the sword has only one edge. The 16th century sources do not offer the same. They begin the fashion of the legal analogy, so it is nice to see that law is at least constant but from the point of view of those who use the swords we get no description. For the sources seen up to this point as well as others that were of no extra value here the use of the word ‘sword’ is more frequent than Backsword by far. This suggests that the Backsword is a distinct object different to the standard two-edged sword.

Silver seems to arbitrarily add the term to his book. It is written for the short sword, yet at some point he refers to the ‘chapter on the Backsword’. Silver must have known that he had not written any chapter on the Backsword. The techniques of the two swords are not differentiated by him so why does he feel the need to add this term? Either it is just an arbitrary term to the English that has no real difference to the short sword, or as it is a civilian term, Silver understands he is speaking to civilians and so chooses to add the term. It certainly appears that Silver himself doesn’t tend towards the term or it would surely appear more often.

All the fencing masters who have written on the sword agree that it is a cut and thrust sword. Silver and all the soldier authors agree that the sword should be around a yard in length along the blade and all the civilian sources seem to agree that it only has one edge so there is consensus. There is an extant archaeological record and if the English nation is collectively using the Backsword and that Backsword has only one edge then the archaeology ought to fit that narrative. The earliest example we have of a basket hilted English sword is from the wreck of the Mary Rose warship. From that sword from the Mary Rose through the collection of the Royal Armouries online, as well as other sources such as Blair’s work, English basket hilted swords are an almost exactly 50% distribution of single and double edge. That is to say that there is no clear preference for basket hilted swords, nor English swords in general towards being single edged. Of course, in the written record there is no mention of a preference but if the Backsword is a single edged, basket hilted weapon of the English that needs to be mentioned frequently by fencing masters, playwrights and poets it would stand to reason that there would be a preference. More to the point if it were the basket hilt that made the weapon then they at least would prefer towards being single edged. Perhaps with another sword type existing alongside it contemporarily but this isn’t the case. No fencing masters treat on any English sword other than the Backsword in their treatises.[36] Either the Backsword is a generic term or there is a preference to single edged swords, Silver is not a fencing master and writes his treatise only on the short sword yet still feels a need to use the term. It is not every single type of single edged sword as English authors often mention other swords such as the sabre, scimitar, cutlass and hanger. By Hope’s definition, the only definition we really have, these swords are not Backswords anyway as they are cutting sword types and the Backsword is a cut and thrust. With all the references to this point it can only be said that 17th century civilians who need an analogy for a single thing with two outcomes and a singular 18th century gentleman definitely see the sword as single edged.

Cultural relevance

The cultural relevance of the sword in the Medieval and post-medieval era cannot be understated. It is often vastly overstated, but the sword does indeed hold a significance to European culture of the 11th-17th centuries. Everyone in the noble classes carries a sword This article focuses on the renaissance period when the political landscape is switching from a feudal, warrior culture to a political mercantile one. The ruling warrior class carry swords as a symbol of their warrior status. The up-and-coming mercantile class carry swords because they are from previous generations of warriors. The culture has not left them yet and neither has it left society as many warriors remain.

Warrior cultures often retain warlike skills as entertainment such as jousts, tournaments, and fighting at the barriers. All these are medieval games based on the skills of war and practiced by those of the ruling warrior class.

‘If two or more doe agree together to play at Barriers, Backsword, Bucklers, Football, or the like, and one of them doth wound or hurt the other, the party hurt shall have no Action of Trespasse against the other, for that it was by consent, and to try their valour, and not to breake the peace’[37]

A lesser-known form of gladiatorial game popular in England is the art of the sword-players. It is not entirely clear in the early days of this art if the players are using swords, blunted sword analogues, or single sticks or cudgels but in the later days of the art the cudgel is the primary weapon used by these players. In the 18th century this weapon is known as a Backsword and in the 19th century becomes known more as a single stick or cudgel. This source suggests that they were also called Backswords in the 17th century

There is a tradition from 18th century country fairs called ‘Backswording’ which is a game of cudgel play. The Cudgel or Backsword play features in the novels of Thomas Hughe, a 19th century author who often wrote of English country traditions.[38] There is also a modern interpretation of the old game of Backswording.

English Country Backswording (ECB) has always been essentially a rustic sport, played by stout yeomen and farm workers throughout the (mainly southern) counties of England and Wales, and often was played by local rules, set by the sticklers at any given match. To win: draw ‘an hinch’ of blood from your opponent’s head.

Although the Victorians developed a form of low-level sabre or cutlass play known as Singlestick, this wasn’t actually the sport of country Backswording as we understand it.

Country Backswording had been played at fairs and revels for centuries and often for high stakes behind as punters in the crowd bet on the Gamester they thought would win. The betting was, of course, largely organised by the cronies of the Sticklers, and bookies and Sticklers shared the takings after each match! The winning gamester would receive a new hat, decorated with a cockade of feathers, or perhaps a new smock! These fellows were, we surmise, largely illiterate, and, as the game was passed down through the generations by word of mouth, little if anything, was written down- but it must be said that references do appear in works of art. Backswording is depicted in the background of a painting by JMW Turner of a country fair somewhere in East Anglia. I’m sorry that I can’t give an exact reference as I’ve only seen it once, I believe it was hanging in a church, but you could google it. Hogarth also illustrated some Backswording and produced an amusing set of caricatures of Gamesters. (ref British Library) This does prove, however, that Backswording was very much alive and part of country life, standing alongside pugilism, shin-kicking and wrestling as a country sport.[39]

It is unknown why the cudgel is known as the Backsword in the 18th century. It may be that the game developed from the use of wasters, wooden replicas of swords historically used in training,

What is known is that the sword-players of the 16th century were known as gladiators and the cudgel players of the 18th and 19th centuries are known as gladiators. This method of swordplay was played for entertainment.

Swordplay as entertainment is ancient and was likely the reason that fencing schools in London played their grading prizes in theatres. George Silver also famously challenged the Italian fencing master Vincentio Saviolo to ‘play’ at many different types of weapons.[40] Silver also notes an altercation with the same Saviolo in Wells, Somerset, where a local Master of Defence also asks Saviolo to ‘play’.[41] There is a distinct difference between sword play, fencing and the fighting of the military. Fencing schools use blunted steel weapons for their training and for their prizes. Despite that injuries do occur. Izaac Kennard is injured on the head so badly that he cannot continue fencing for that day.[42] In the sport of Backswording, sword-players fight until they draw an inch of blood.

The sources that use the term Backsword often also use the term sword, which is no surprise of course. But it offers a view of the relevance of the Backsword in its culture. There is a question to be asked as to why the Backsword needs to be specified by the people of its time. If the sword is the same as the two-edged sword in form and function, then why does anyone need to distinguish it? If it is a cudgel, then why doe fencing masters use them? A scimitar or a falchion are different swords to a short sword and have plausible reason to distinguish it. Their form and function are considerably different. The Backsword seems to have a significant cultural relevance as a sword for gladiators, a sword for fencing masters and a useful analogy for everyone else.

The analogy of the law makes for one good reason to distinguish the Backsword, the author needs a sharp and a blunt consequence from a single action and a single edged sword offers exactly that. The problem is that any single edge sword would facilitate this analogy. In the 1627 play ‘The Pheonix’ a lawyer lists his ‘Weapons of law’. A longsword is a writ of delay, a rapier and dagger, a writ of execution and the Backsword is a ‘Scandala Magnatum’ a libel against a gentile, a person of high office. The response ‘Scandals are back-swords indeede’ A damage to reputation or cause for offence. This source appears to see the Backsword as something not a weapon of nobility.

Sword-players would most certainly not have been within the gentry class, but neither would they have been from what we call the peasant class.[43] They would most likely have come from the Yeoman class, those who are not unwealthy but do need to work to make a living. Many soldiers would come from this class. This may be the reference to being an ungentlemanly weapon. Being a sword player is not seen as a good thing socially. In a book of interpreting dreams the author tells us ‘To se himselfe mad or become a sword player, signifyeth condēnation. And to see sword players , that thy enemyes shal ouer come thee.’[44] And another reference in a book concerned with the correct education of children, written by a schoolmaster speaks of fencing highly as good for the mind and body but of being a sword player he is less complimentary

‘All these sortes of fensing were vsed in the olde time, and none of them is now to be refused, seing the same effectes remaine, both for the health of our bodies, and the helpe of our countries. That kinde of fensing or rather that misuse of the weapon, which the Romane sword players vsed, to slash one an other yea euen till they slew, the people and princes to looking on, and deliting in the butcherie, I must needes cōdemne, as an euident argument of most cruell immanitie, and beyond all barbarous, in cold blood, to be so bloodie.’[45]

Though being a fencing master is to be revered

Againe whose name is renowmed, his doynges from time to tyme wil be thought more wonderfull, and greater promises wil men make vnto them selues of suche mens aduentures in any commune affaires, than of others, whose vertues are not yet knowne. A notable Master of fence is marueilouse to beholde, and men looke earnestly to see hym doe some wonder, howe muche more will they looke when they heare tel that a noble Captaine, & an aduenturouse Prince shal take vpon hym the defence, and sauegarde of his countrie against the ragyng attemptes of his enemies?[46]

A sentiment shared by George Silver in his work.

The continued use of the term Backsword from Ms.2530 right the way into the 20th century suggests that there is a reason to distinguish the Backsword from other sword types. It is a civilian rather than a military term, though both a civilian and military weapon. In writing it appears in the 16th century, becomes prevalent in the 17th century and is mentioned by fencing masters of the 18th century. It is used casually as a term for a single sword by the masters of defence and Silver sees it as the same weapon as the short sword. Fencing treatises of the 17th century are scarce so evidence relies on civilian works for that 100-year period. The reason there is such an increase in use of the term in the 17th century is possibly due to the availability of printing more so than an actual increase in common usage. Prior to this printing is a very expensive endeavour, during the renaissance it becomes much more available to many more people of lower estates than it had previously been. By the 18th century the term arrives again in the works of fencing masters, though they don’t seem to have a clear message on the sword. Zach Wylde, an English gentleman writing in 1711 says ‘Back or Broad-Sword, is a true English weapon and first made use of in this nation’. Donald McBane adds the Back-sword into his treaty under the title of ‘General Directions of the Guards of the Spadroon or Shearing-Sword’ suggesting that he considers the Backsword to be somewhat synonymous with these weapons. In that same chapter he speaks of coming up against ‘A man with a Broad-Sword and Targe’ so it may be considered he thinks the Broadsword is different to the Backsword, spadroon and shearing sword. Like to Wylde, Andrew Lonnergan describes the ‘English broad or back-Sword’. Only Hope offers a description of three different swords with three different ways to use them.

Ms. 2530 although a record appears to not be a constant record from its inception, rather a copy of an earlier document.[47] If this is the case there is a possibility that the term ‘Backsword’ has been transcribed as such due to the popularity of the term or the weapon at the time it was copied. This seems unreasonable for a copy of a record and improbable as the record continues into the time of the scribe and is written by several different hands. However, if we concede that the record was copied accurately and the term has been used since the time of Henry VIII then we should also look at the weapons being used by the people of that time.

The Field of the Cloth of Gold is a painting said to be completed around 1540 depicting a summit meeting between Henry VIII and the king of France, Frances I. This image shows the procession of Henry VIII and his retinue towards the field. It also shows many people standing watching. A great many of the watchers as well as some of the soldiers in the retinue are carrying swords with basket style hilts.

The same can be seen in the Embarkation of Henry VIII at Dover. Another image painted to commemorate the field of the cloth of gold meeting. This time showing Henry and his retinue boarding their ships bound for Calais. This image also shows many people carrying swords with basket hilts. Another good image for the same is the portrait of (probably) William Palmer.[48] This portrait is of one of Henry VIII’s Gentleman pensioners and at his side he has his hand on the golden hilt of a basket hilted sword.

These images are all important because they show the most common weapon being carried by the English is the basket hilted short sword. Although we cannot see how many edges the swords have, that does not mean that these swords are called Backswords by the people carrying them nor does it mean that they do not call any cut and thrust sword a Backsword. As these images are from early in the history of the basket hilted sword it is plausible that the use of the term is as generic as it is to Silver or the Masters of Defence from Ms. 2530. Whatever the weapon is it is very clear that it persists consistently throughout 250 years of English history and is an important symbol to those who carry it.

The basket hilt goes through a lot of changes in its time, though it would be presumptuous to suggest a linear development of any complex hilt design. From the first iteration of hilt complexity blacksmiths would have had the skills required to manufacture any hilt design that was imagined from that point onwards.[49] Although developments across time are often attributed to sword designs it is a dangerous path. There are however trends from the designs of the Mary Rose sword and variations of that to the Mortuary style hilts in the 17th century. Swords lose their quillons around the 17th century, and the English sword in particular gets inspiration from the Dutch and Belgian Walloon hilts in the 18th century, but the sword persists not only in the scabbards of the English but also in their hearts and minds. It is my opinion the last of the English Backswords is the 1788 heavy cavalry sword, a straight, single edged, basket hilted sword with a 36” blade. The centralisation of the military and the instigation of patterns for military swords begins the homogenisation of swords and the end of all diversity within them. The use of the sword has essentially left the soldier by this time anyway. Today, the swords held by Military personnel are symbolic only.

Playing, fencing and fighting in England are distinct activities. Often when the term ‘Fencer’ is used it is referring to travelling entertainers, the sword players, rather than those who frequent fencing schools. In 1572 Elizabeth I set out an act for the punishment of vagabonds, and for relief of the poor and impotent in which part 5 notes ‘For the full expressing what persons shall be intended within this branch to be Rougues, vagabonds and Sturdy Beggars’ which includes ‘all fencers, bearwards, common players in interludes and mistrels, not belonging to any baron of this realm…Which said fencers [&c.] shall wander abroad and have not license of two justices of the peace…shall be deemed rogues, vagabonds and sturdy beggars’.[50] Similarly those who frequent fencing schools are not necessarily soldiers, ‘The blades of their daggers also, I would wish them to be not above 10 inches long, and that the hilts of the same should be only made of one single and short cross without any ports, or hilts at all, and not with great hilts after the fencers or alehouse fashion’,[51] ‘For a man haunting long the wars, and seeing little execution, is as one that uses often the Fence-schools, but never takes weapon in hand’.[52] though the art of fencing from the fencing schools and the art of the soldier are complimentary. The art of the sword-player is more closely related to the fence-schools. All three sisters from the same parent.

Redefining the Backsword

With such a high importance placed on the weapon by its historical users it seems unfair that now it gets banded in with another weapon that is, rightly, held in great esteem by its own nation. Surely the Scottish nation wants the history of their Great Sword to be as individual as the History of the English Backsword. Surely both swords deserve the recognition of their own individual traits rather than just to be thrown in together.

One reason modern users believe that the Backsword and the Broadsword are the same weapon could be that the later historical texts seem to put them together. This reason may well have been exacerbated by Claude Blair. Even as Blair wrote his work on the basket hilt in 1981 he covered many important Early English swords but as he was studying the source of the highland hilt it is no surprise he saw no reason to distinguish Backsword from Broadsword.

Hope and his definition of three different blade types is the main distinction between the Backsword and Broadsword. A good secondary reason to split the two weapons is the lack of any historical reference prior to William Hope in 1691.[53] Or any archaeological object dated before 1600. I think it is important to separate these two swords before trying to conclude on the Backsword.

The Scottish or Highland Broadsword is a short basket hilted sword used by the Scottish from around 1600. Blair notes in his basket hilt article that there is often the use of the term ‘Highland Hilt’ in the 17th century with the earliest reference being from 1576 though he concludes that ‘Highland Hilt’ does not ever conclusively describe a basket hilt so we cannot put the highland Broadsword earlier than 1600.[54]

The highland Broadsword is more likely to have arrived sometime after 1603. In 1603 Queen Elizabeth I died and the throne of England was passed to King James VI of Scotland. When this happens, the king brings his entire court with him to London. This influx of Scottish courtiers could easily have been influenced by English fashions, and they took to using the English sword. From there the Scottish developed their own sword whilst the English carried on with their designs too.

The hilt of the Scottish Broadsword is smaller than that of the English hilt style and often extends quite far up the hand. This restricts the ability of the hand to move inside the basket and makes elongating the grip for thrusting impossible. As the hand is stunted into what is usually referred to as the ‘hammer’ grip in modern fencing, the sword must be either turned around the wrist as 18th century fencing tends towards or moved around by the elbow and body with no movement of the wrist. Of course, the Broadsword can thrust as any sword is technically capable of both cutting and thrusting, but the Broadsword hilt design combined with the mass distribution tends towards the cut. The sword blade itself is usually quite short at around 83cm – 86cm long.

The hilts of English swords do not restrict the hand as much. Most commonly in the 16th century preferring only three panels and just two for the 17th century trends. In one of George Silver’s rare moments of clarity he tells us in detail two different ways to hold the sword.

‘Remember in putting forth your sword point to make your space narrow, when he lies upon his Stocata, or any thrust, you must hold the handle thereof as it were along your hand, resting the pommel thereof in the hollow part of the middle of the heel of your hand towards the wrist, & the former part of the handle must be held between the forefinger & thumb, without the middle joint of the forefinger towards the top thereof, holding that finger somewhat straight out gripping round your handle with your other 3 fingers, & laying your thumb straight towards his, the better to be able to perform this action perfectly, for if you grip your handle close overthwart in your hand, then you cannot lay your point straight upon his to make your space narrow, but that your point will still lie too wide to do the same in due time, & this is the best way to hold your sword in all kinds of variable fight.

But upon your guardant or open fight then hold it with full gripping it in your hand, & not laying your thumb along the handle, as some use, then shall you never be able to strongly to ward a strong blow.’[55]